There has been a full spread of recent articles around the United States' largest planned wind farm this week. Weighing in at 800 MW and based in Massachusetts, it far outweighs the next largest offshore wind farm in America, first generation expected in 2 years. However, it is smaller than the largest existing wind-farms already operating for some years in Europe. There could be an argument that an absence of favourable regulatory and subsidy support from government had slowed progress in wind power roll out in America.

This comes against a backdrop of a 30 GW planned wind power capacity strategy and subsidies to back the plan and deliver by 2030. This gives the country ample chance to reach the goal, and leverage their significant, albeit concentrated wind resources. The below chart highlights the wind capacity by state, as of year-end 2018, with most capacity centred around the centre-south and far West of the nation.

What Kind of Support does a Renewable Project Tender offer to Constructors?

There are various methods to price and design a tender for renewable capacity. The main ones used by national energy and resource bureaus, I had covered lightly in a previous post. The support and subsidies for wind are slightly different to the nature of subsidies which are used for fossil fuel production and power generation, covered briefly below (more detail here). These subsidies are, in some cases, directly proportional to the market price for electricity.

Feed In tariffs (FIT)

In this deal, renewable generators are paid a fixed sum regardless of the wholesale price of electricity. This kind of contract with generators offers significant price risk for those locked into the contract. This is especially relevant given the expected deflation in energy prices because of renewables, coupled with distributed energy storage expected to roll out this decade. Now You Know channel covered just this topic a month ago, leaning in to LCOE discussions and the impact on hydrocarbon power generation assets.

Just this week, it was revealed that a mothballed coal plant was brought back online purely to power bitcoin mining units. Being applied in a very specific way, and the balanced operating cost against possible bitcoin awards (especially considering where informed persons expect the price to go), the operator clearly sees a cost of energy which isn't prohibitive in this case.

These tariffs were also popular with encouraging home investment by private individuals in the UK before the FIT was severely curtailed back in 2012, before being eliminated entirely in 2019.

In Europe FIT is still widely popular, Belgium and Germany are a case in point. It is not uncommon for home solar installations to propagate there, however, not without controversy since the Belgian Feed-in-tariff had been canned in 2020.

Feed-in Premium (Fixed)

This price-based policy dishes out a fixed premium payment per MWh generated, on top of the market wholesale rate / MWh. The wholesale rate will move with the market, but the premium is fixed. Long term - inflation can eat into the value of this premium and generators need to be sure that they can sustain the or even increase the amount of MWh they produce (either through debottlenecking of maintenance, more likely rationalising and shortening maintenance periods and unplanned downtime, etc). DNV is a risk management organisation and a source of detailed energy industry data. They and others are looking at operations risk management closely.

Feed-in Premium (Floating)

Similar to the fixed price instrument above, however here the generator receives their premium calculated as the difference between some agreed minimum price and a forward looking wholesale price. I would imagine such agreements also have triggers for tail-risk events such that the wholesale price exceeds or falls below the guaranteed price during some rare market event (think cover shutdowns reducing energy demand in some specific context).

Contracts for Difference

Contracts here are similar to the floating premium above, but if the wholesale price exceeds the guaranteed price, this surplus is repaid by the generators, returned to the counter-party.

Zero-subsidy bids

Also known as the "Dutch Model" Here, generators bid against each other to for rights to build a wind farm. Price is not the selection criteria for this model. Qualitative assessments are made of the bids, considering capacity, quality of design (do not under-estimate this - reliability, maintainability, human factors (also read as Ergonomics), risk analysis are considered.

Here, the constructor bears all the cost of generation and collects only the wholesale price, whatever contracts (Power Purchase Agreements (often 10, 15, 20 years or so)) they can arrange with their off take partners. In this model, it is often that the government will absorb transmission costs for the project.

Green Certificates

This mechanism is similar to carbon trading, in that the renewable power generated is accompanied 'on paper' by the creation, minting of renewable energy certificates. These certificates themselves also offer a revenue stream as their sale are also done on the open market and often have a guaranteed minimum prices in those markets as governments push policy objectives on lower carbon.

Reading between the lines, from the perspective of a 'client' government, it makes sense to encourage a price here to draw a punitive cost of carbon. However, on the other hand, too hard a cost on those certificates could incentivise 'customer' companies to relocate - this is especially true of larger companies the capacity in multiple markets.

What Subsidies are available for European Wind Projects?

In Europe - covered my previous article - there are different tariffs models - these tariffs incorporate a certain level of governmental subsidy to meet agreed targets for renewable energy production.

How do things stack up in America?

This article covers only the subsidies related to Renewable generation. This is a separate point to the contention about the balance between Renewables and Fossil Fuel industry subsidies. Briefly, approximately 6.5% of Global GDP was spent on Fossil Fuel subsidies in 2017, amounting to $ 5.2 T in total. China spent the lion's share at $ 1.4 T in 2014 (last accurate figure from the IMF), followed by the US, with $ 649 B, of which 80% supported oil and gas, and 20% went towards coal projects.

We cannot overlook China's developing market and need for net increase in power generation, even if this does include some fossil fuel use. There are some strong arguments against deploying fossil fuel technology in developing countries, citing the 'future is here' and encouraging renewable deployment. We will not explore these arguments here, but there is plenty of material online. Perhaps to cover in a future article.

This article specifically covers the risks and benefits for investors and the government bureau's approving tender wins to those companies. However, given that overall subsidies to fossil fuel industries (not only the generators using fossil fuels) attract 80% of all energy subsidies globally, there could be some argument for countries to fulfil the calls from the International Energy Agency, and the European Union.

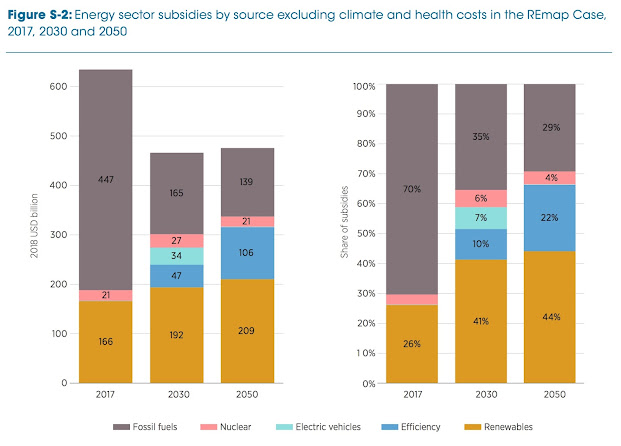

Cut from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) 2017 Renewables/ subsidy report. Credit IRENA. Note that the expectation is a progressive reduction in subsidies overall to the energy sector, however, the lion's share of change comes from removing fossil fuel subsidies.Shifting the balance toward renewables, perhaps further incentivising and through careful tender requirement design, could redirect taxpayer dollars as a lever to accelerate renewable energy transition.

The challenge to flatly removing the subsidies for fossil fuels comes because they are tax related and related to widely accepted depreciation metrics. These are standard methods that even the smallest companies use to discount the value of their assets over time as part of tax accounting. However, given their fossil fuel context, it could be a fair move from governments to flatly write those measures into history. To this point, some rumblings had been in the submission of "Clean Energy for America Act" (S:1288) and the "Financing Our Energy Future Act (S. 1841): Formerly the MLP Parity Act".

These reform bills, currently in consideration, aim to rationalise a complex tax subsidy framework into 3 technology-agnostic tax interventions, and appeal to extend the Master-Limited Partnerships, corporate and tax structures favoured by incumbent fossil fuel energy majors, to renewable energy companies. This move would help by reducing the tax burden to renewable companies, while also establishing the fairer playing field in this respect to the structures of incumbent energy majors.

What Renewable Subsidies are planned under Biden's Energy Plan?

Earlier in 2021, a $ 2.25 Trillion American Renewable Infrastructure Blueprint was approved by the Biden-Harris Administration. A key component as it bears on renewables generation is a 10 year extension of the existing federal renewable subsidies.

There is also provision in the proposal, for extending an electric vehicle point of sale subsidy for electric vehicles. Currently, these subsidies exclude companies which manufacture more than 200k vehicles per year, and run to $7,500 per vehicle. Releasing this restriction puts Tesla and GM (leaders in electric vehicle volume production) back into frame and helps more consumers to make a switch to drive electric.

However, these latter levers do not impact on the renewable energy generation sector, only commercial and consumer transport. For insight into the impact on generation, we need to look at the existing subsidy levers discussed below.

How do US subsidies apply to energy projects already?

As it stands, a great report from the US Energy Information Administration reports that there are 4 key levers to support renewables (these levers are also in place for non-renewable generation).

1) Tax adjustment - By doling out rebates and reduced tax rates for companies throughout the value chain (end to end from manufacturing, construction, operators, decommissioning works) interventions in tax burdens can support players in the wind value chain. I would hope for detailed retrospectives by government to understand the value received (additional capacity, local advanced manufacturing jobs added) for the investment.

2) Direct spending on projects - Here the government takes the place of the investors backing an investment in renewable assets, assuming all the risk.

3) Research and Development - I believe that investment in continuous improvement in manufacturing, operations and decommissioning can be a critical investment that will underpin the industry. By investing to learn more and lower the total cost of ownership both of an asset, an asset type, and remove inefficiency in the end to end value chain, the government and lower the risk and increase the capital efficiency in renewable projects.

4) DOE Loan Guarantees - This is a similar approach to the Green Investment Bank established by the UK government - now privatised - sold to Macquarie Holdings. Rebranded Green Investment Holdings, the group is free to invest in overseas green projects. In a rare example for a UK government privatisation move, this one turned a profit of 10% over the 5 years that the government had established and operated the bank (£186 MM total). My point here is that by backing loans and giving guarantees, the government becomes a backstop and assumes capital risk for the project, overcoming the hesitance around innovation-themed projects.

You can reach me on Twitter @Ronnie_Writes

Comments

Post a Comment